By Ciara Rouege

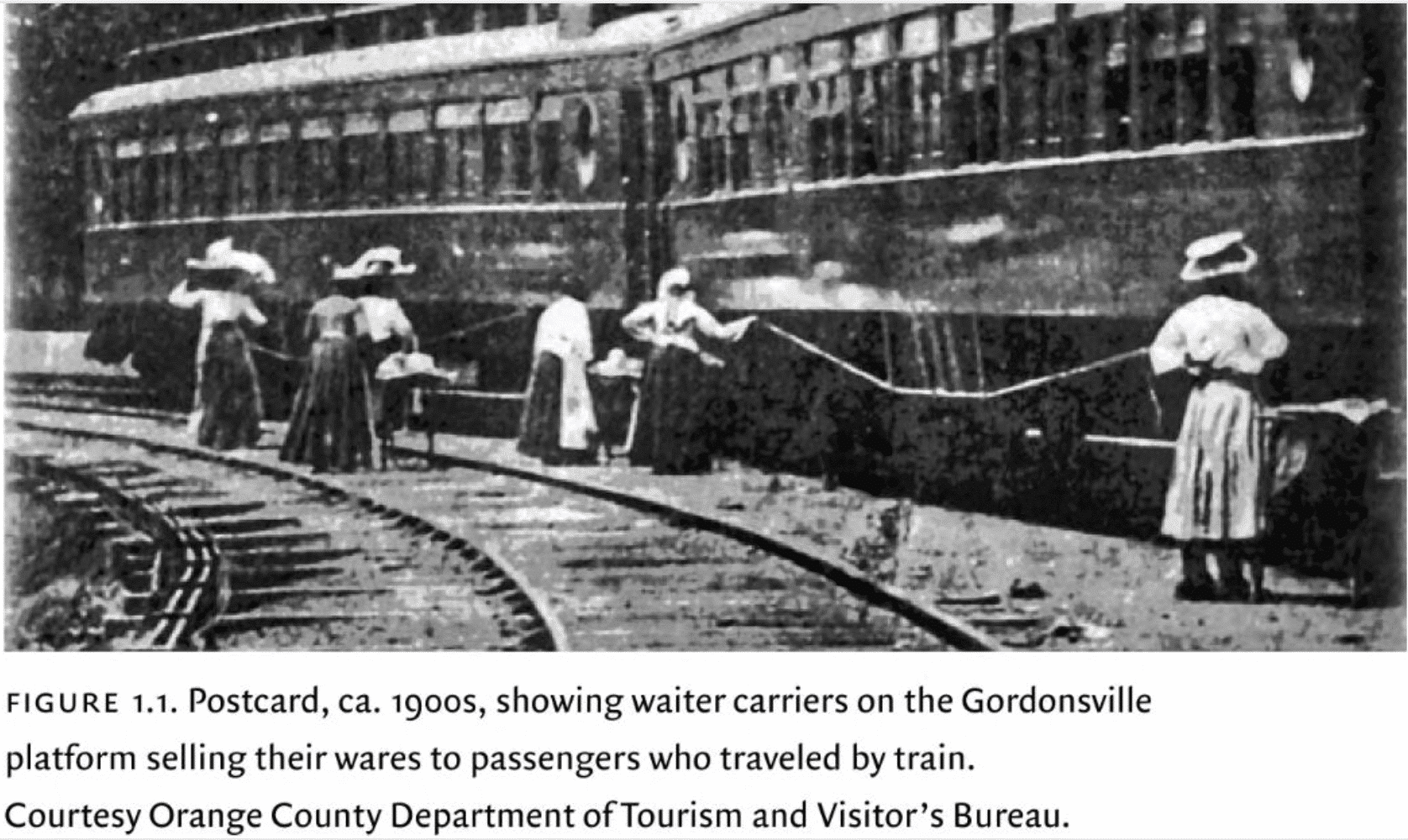

Not only is food foundational to Black culture, it’s been a crucial part of building and maintaining Black wealth in America. In the post-Emancipation period and into the 1940s, newly freed Blacks — who were banned from most workplaces — turned their domestic skills and knowledge of animal husbandry into a source of income. As Psyche A. Williams-Forson put it in her book, “Building Houses Out of Chicken Legs: Black Women, Food and Power,” “chicken was more than a source of nourishment; it was their livelihood.” Entrepreneurial Black women in places like Gordonsville, VA seized the opportunities inherent to railroad expansion by dubbing themselves “waiter carriers” and selling home cooked plates of biscuits and fried chicken to hungry travelers.

RELATED: The Best Black-Owned Hot Chicken Outside of Nashville

While some Blacks were able to turn home cooked pound cakes and fish plates into licensed culinary businesses, the earning potential for other Black chefs was either cut short or cut altogether by commercial cooking laws. Such laws barred those who didn’t have the means to transition to commercial kitchens from legally profiting off their culinary talents and skills.

However, as modern times have seen the rise of the “eat local” and DIY movements, many states have eased restrictions on home cooks by introducing cottage food laws, which are empowering home cooks and bakers to turn informal side hustles into legitimate streams of income.

Cottage Industries

According to Pew Charitable Trusts, cottage-food laws allow home-kitchen cooks to make and sell non-hazardous foods that have a low risk of causing food borne illness. Those items typically include baked goods, jams, jellies, and other products that don’t require time and temperature controls for food safety. Only 23 states and the District of Columbia require a permit or license to operate a cottage kitchen through cottage food laws, which often includes fees, signing up for a state mandated course and often home inspections. In the remaining states, cottage food providers are automatically given legal protections as long as they’re operating within certain “umbrella” rules. It all amounts to legal cover for the multi-billion dollar local food industry, which saw an increase in popularity at the beginning of COVID.

RELATED: Edibles & Canna Cooking with LaWann Stribling

Robin Caldwell, a food historian and recognized cottage kitchen expert, says she noticed a surge in Black-owned cottage food kitchens in the early days of the coronavirus, as the pandemic put millions of Americans out of work and compromised the incomes of others placed on furlough or reduced hours.

“People are now looking at their own culinary skills or something they do well and turning them into side hustles and ways to bring extra income into their homes,” Caldwell said in an interview with Black Restaurant Week.

Baked goods are among the most common types of food sold out of cottage kitchens, and according to Caldwell, women outnumber men in this timeless industry.

Taking Matters Into Our Own Hands

It was a craving for tasty vegan donuts that inspired Kapreta Johnson to get into the cottage kitchen game. She established Brown Suga Vegan in Arlington, Texas in the summer of 2020.

“Being vegan, it was hard to find donuts online,” Johnson said. “I had bought some stuff online but by the time it arrived, the craving was gone.”

Johnson decided to take matters into her own hands one morning, going into the kitchen and baking her own donuts and other treats. She would post her creations on social media and get a strong reaction— that’s when she realized there was a market for vegan donuts.

She says the hardest part about running a cottage kitchen has been time and space, as Johnson operates her business out of her home.

“Baking is very time consuming,” Johnson says. “It can take up to 12 hours just to bake everything and get it ready for distribution. That’s definitely one of the challenges because you’re not dealing with an industrial kitchen; there’s only so much you can bake and set aside.”

RELATED: 5 Black Women-Owned Bakeries (including ones with national shipping)

Johnson strongly recommends getting a food handler’s license to educate yourself about the basic dos and don’ts of maintaining a cottage kitchen. It’s also beneficial because some farmer’s markets require them. She added that Brown Suga Vegan is a certified business with the state.

Texas doesn’t require a cottage kitchen permit but products must be labeled as cottage food and can only be sold directly to customers. Johnson arranges pickups with her customers, but she also sells at farmer’s markets and pop-ups.

“If [Texas] moved to where permits and certifications are required, you’ll have less of those start-up companies that are cottage kitchens or catering services because it’s just so expensive,” Johnson said. “If you’re just starting out, you’re going to be in the hole for a while because you’re just getting into the market.”

Samiyah Sumpter, who runs Doux Vegan Donuts out of her apartment in Atlanta, paid a $150 licensing fee and additional costs for a state-mandated class. She described the course as lengthy and intensive but helpful. She also underwent a home inspection.

RELATED: Recipe: Vegan Blackberry Donuts

“I think just to protect people those certifications are more than necessary,” Sumpter said. “And even if you have good intentions, there are just things that you don’t know about food safety that you should. Like some people really don’t think they should wear gloves.”

Challenges & Opportunities

Many Black-owned cottage kitchens face the same obstacles as Black entrepreneurs in other industries — such as acquiring bank loans — especially when it comes to transitioning into commercial operations. Some draw parallels to the position that many Black entrepreneurs face in the once criminalized, but now increasingly legal, cannabis industry.

“A lot of Black and brown people are thrown into jail for misdemeanors— now they have a record. Obviously, now medical marijuana becomes a thing,” Caldwell said. “For the people who suffer the most, it just becomes their underground economy as opposed to an economy.”

But despite the structural challenges facing Black food-based businesses, more and more opportunities are being created to connect small-time sellers with large, hungry buyers.

Outlets like Black Restaurant Week’s HRVST Marketplace are creating opportunities to help cottage kitchen owners and other culinary professionals take their businesses to the next level. Featuring things like Black-owned home goods, recipe cards, cookbooks, and kitchen gadgets, vendors will have digital storefronts to manage orders and shipping, and their products will be featured and promoted in the Black Restaurant Week and Latin Restaurant Week digital network.