The Chicken Hut’s place in Durham, N.C. continues to draw new and loyal customers 65 years later.

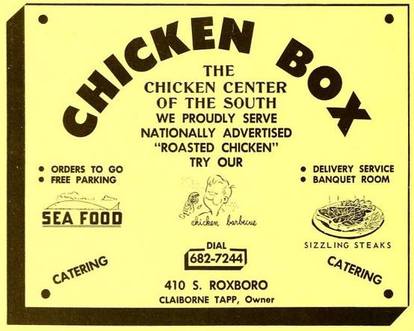

Crispy golden skin. Insanely juicy meat. Fresh off the fryer. Seasoned to perfection. This is the famous chicken that cemented The Chicken Hut’s place in Durham, N.C.’s soul food scene and continues to draw new and loyal customers 65 years later.

Established in 1957 by Peggy and Claiborne Tapp Jr., The Chicken Hut is the longest continuously operating Black-owned restaurant in the city and the second longest in all of Durham. Now managed by their son and daughter-in-law, Tre and Khya Tapp, the beloved eatery managed to stay open and fully staffed throughout the pandemic, with not even a single day of closure.

Placed against the backdrop of the past few years, which have been marked by shutdowns, labor shortages, inflation, and supply chain issues – that’s a miracle. But given the storms that The Chicken Hut has weathered over the past several decades – systemic racism, economic downturns, the digital revolution and more – it’s not surprising. Through it all, Black Diamond Restaurants like The Chicken Hut could teach a master class on both sustenance and survival.

Survival

Though Tulsa, Okla.’s Greenwood district has gotten a lot of attention in pop culture and social media in recent years, it wasn’t the country’s only “Black Wall Street.” Established mostly during the period of Reconstruction and often lasting through Jim Crow, thriving commercial districts in and around Black communities existed throughout the United States. Chicago had Bronzeville; Atlanta had Sweet Auburn; Little Rock, Ark. had West Ninth Street; and Jackson, Miss. had Farish Street. Durham had a neighborhood called Hayti, where the Chicken Hut – then called the Chicken Box – was originally located.

In a 1994 Duke University oral history interview, Peggy recounts fond memories of a thriving stream of Black businesses in her hometown – everything from dry cleaners, restaurants, and barbershops to banks, churches, and even a hotel.

While Tulsa’s Greenwood District was taken out in an exceptionally brutal and chaotic fashion, others often died a slower, somewhat surgical death. In addition to policies like redlining, the government’s urban renewal projects – which started with the Housing Act of 1949 and lasted through the early 70s – and the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 carved up these neighborhoods, sending waves of devastation throughout Black communities.

For the urban renewal projects in particular, “The idea was ‘let’s get rid of the blight,’ Joseph DiMento, a law professor who co-wrote Changing Lanes: Visions and Histories of Urban Freeways, told Vox. But modern historians are challenging what seems to have been the government’s definition of blight. “Places that we’d now see as interesting, multi-ethnic areas were viewed as blight,” DiMento says.

The article continued: “Highways were a tool for justifying the destruction of many of these areas.”

Ultimately, the projects resulted in mass displacement and dispossession in Black communities like Hayti. The location for the original Chicken Hut was one of those casualties, displaced to make space for North Carolina Highway 147 or the Durham Freeway.

“Urban renewal came by and wiped everybody out,” Peggy says.

But they survived. Peggy and Claiborne regrouped and settled into their permanent location on 3019 Fayetteville St. at the height of the Civil Rights Movement. Far from idle observers, they fed the movement by bringing food to freedom fighters who participated in sit-ins and peaceful protestors who were held in jailhouses.

It’s that commitment to community – and adaptability – that has helped the Tapps remain in operation for more than six decades. They also have a stellar set of business practices that were handed down from one generation to the next.

Service

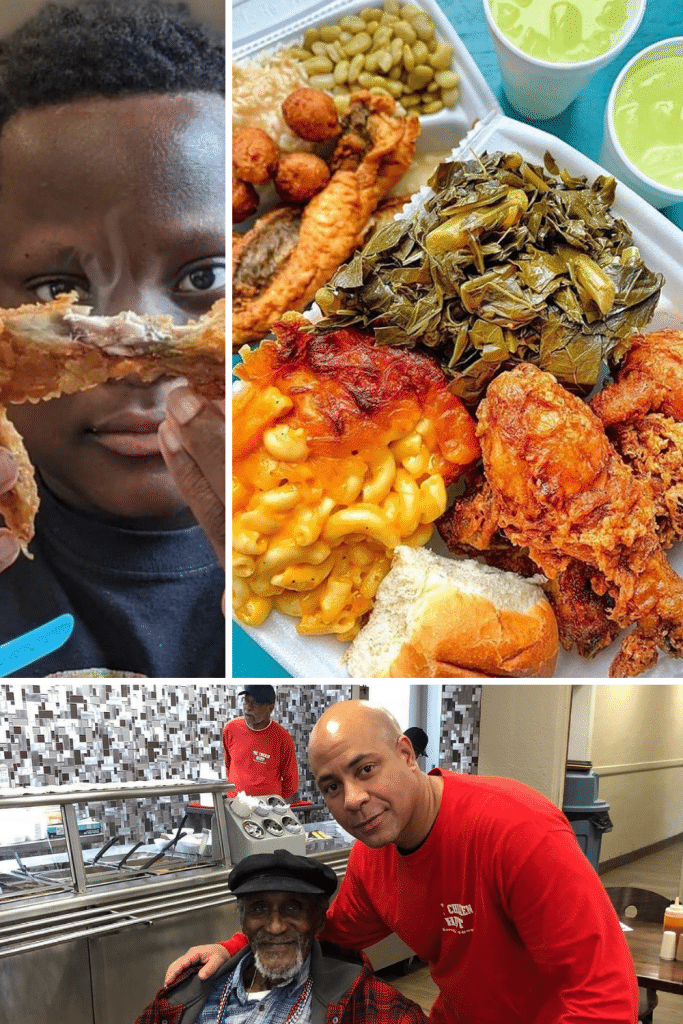

For many customers, The Chicken Hut feels like home – a place regulars are easily remembered by their name and order, and first timers are warmly welcomed. One reviewer captures it well: “They wrote the book on customer service.”

Great customer service is one of the hallmarks of longevity for many great restaurants, and according to Khya Tapp, a lot of that can be attributed to having a good team.

“Hire well,” she advises. “If you can get lucky to have a good team, that’s so important because they’re the face of the business.”

Just as employees pour into customers, Tre is intentional about pouring into his team by celebrating birthdays and arranging school pickups for employees with children. Supporting the families and home lives of their employees may be modern or innovative at a time when people are demanding more work-life balance, but for The Chicken Hut and The Tapps, that isn’t anything new.

Sustainability

Claiborne passed away in 1998, with Peggy passing away 20 years later in 2018. Peggy had worked there since she was 16 years old and instilled the legacy of great service that Tre proudly carries. The younger Tapp leveraged that legacy to help The Chicken Hut weather yet another storm: technology and the digital revolution.

“For so many years, we were just about word of mouth. But when Tre stepped in, he knew how important it was to reach the younger generation,” said Khya. “We started connecting with social media and that’s what’s really helped us get the word out there.”

The digital word is filled with stories of kindness, like one person who was running short on cash and instead of being turned away, was told to just come again next time; or a group of 11 out of towners who pulled up to the restaurant after it had closed but were still offered freshly fried chicken; or alumni from North Carolina Central University who make it a point to stop by during homecoming.

There are dozens of posts and reviews like this – a testament to The Chicken Hut’s resilient recipe for success: fresh, made to order, affordable meals and an abundance of genuine hospitality.

Photo credits:

@sujungchronicl

@

@

@locnlovely

Author: Black Restaurant Week

Content Team