Iman Haggag, the chef and owner of POTs, did not cook much when she lived in Cairo. Despite having a deep love for Egyptian food, she didn’t learn to start cooking it until she moved to Las Vegas in 2006. Absence makes the heart grow hungry.

“It was a little bit out of survival mode,” she tells Black Restaurant Week. “Our culture is not really conducive to fast food or eating out unless it’s a celebratory event, so I’m used to eating at home. [When I moved here,] I had to kind of remember what food tasted like.”

She had to start from scratch, hopping on Google to research the basics of the food she grew up eating, from the agriculture and the spices to the techniques and equipment. “My philosophy is that you cannot move forward without looking back and seeing the steps behind you,” she says. “It became more like a puzzle I wanted to solve than just food.” Soon, her family and friends began raving about her take on traditional Egyptian food. Her confidence grew and the idea for POTs – Las Vegas’ first Egyptian eatery – was born.

For this year’s Africa Day, Black Restaurant Week spoke with Chef Iman about POTs and the basics of Egyptian food.

RELATED: How the Diaspora is Reconnecting to Africa Through Food

Egyptian Food 101: Ancient Grains

“Lentils are one of the oldest crops ever recorded,” Iman says, citing the legume’s 13,000-year history on the planet. Fava beans, lentils, chickpeas, wheat and ancient grains are almost as old, and each play a key role in the cuisine of Earth’s oldest known civilization. “Those are all embedded in the starting of civilization,” she says. “And we’re still consuming the same line of food today.”

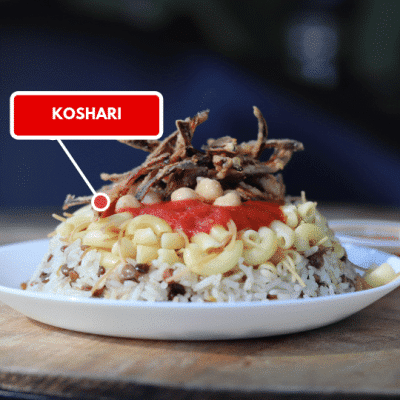

Koshari, a popular street food, was eaten by the pharos, and the nutritious, vegan dish is still eaten by people of all ages and income levels. The ingredients have evolved slightly since its origins, but today it includes rice, lentils, pasta, tomato sauce and chickpeas.

Speaking of chickpeas, Egyptians are adamant about the idea that falafels originated in Egypt. “This is very controversial,” Iman says, laughing. Just like Ghanaians and Nigerians wage the Jollof wars, Egyptians and their Middle Eastern neighbors go back and forth over who created the deep-friend fritters made from ground chickpeas and/or fava beans. But one way to look at the dish – and Egyptian cuisine in general – is as a melting pot of various regional flavors.

“We had minorities that were living in Egypt for so long – the Romans, the Greeks, the Turks,” Iman says. “So we’ve had a lot of influences.”

RELATED: 5 Types of West African Rice

Egyptian Food 101: The Spices

“We use a lot of hot red pepper,” Iman says. “But we are most famous for our coriander. Our coriander is very, very high in quality and it’s used all over the world, in the finest dining you can find.”

The food is also filled with crops like leeks, garlic, shallots, scallions and chives, as Egypt’s environmental profile is optimal for growing alliums. They are reflected in the dishes served at POTs, like the lentil soup, which is topped with fried onions.

“I wanted to make sure I represented authenticity,” she says. “Not just in the flavor but in the agriculture itself.”

Egyptian Food 101: Tools & Techniques

“A lot of people ask why it’s called POTs, so we give them a little lesson,” she says. “POTs is a reflection of the different kettles and pots we use for different foods.”

For example, the fava bean pot was invented in the 11th century and is often so big that it can’t be set on the stove. Traditionally, Egyptians would bury the pots under hot coals and let the food steam all night so people could eat later in the day.

Slow cooking techniques are important to Egyptian cuisine, though preparation methods and ingredients can vary based on the region. Plates in the coastal areas are often seafood heavy, with lots of wood firing.

In the South, which is closer to Sudan and Central Africa, long-cooking stews over slow simmering fires in mud ovens are still in use today. “In the South, it’s more of an artisan, hands-on, basic, older way of cooking,” she says. “It will be the most flavorful food you ever had.”

Egyptian Food 101: Traditions

“Food is always entwined with people’s celebrations and mourning’s. And we have that every other day,” Iman notes. She described one cookie in particular as one of the most popular celebratory foods.

“After the month of fasting, every house in Egypt had to have these,” she said. “It’s filled with a lot of cashews, pecans or pistachios, and dates.” The cookies are eaten at all manner of family events, but especially after Ramadan.

“From the richest families to the poorest, all of them have their own version of these cookies,” she says. “So anytime, you can go to any house and knock on the door and ask for some of these cookies. And somebody will bring you some.”

Click here for Iman’s recipe for Eid cookies.

Select Highlights from the POTs menu:

- Egyptian Fries – Fried potato topped with Egyptian doqqa (contains Almond)

- Falafel Samosas – Crispy dough stuffed with our famous falafel batter and harissa, drizzled with roasted red bell pepper sauce

- Ful Mudammas – Fava beans slow-cooked with your choice of olive or flaxseed oil, assorted vegetables, mix greens, salata Baladi and topped with your choice of regular or spicy tahini sauce

- Egy Bak – Baklava Egyptian way stuffed with dried fruits and topped with walnuts and a drizzle of sugar cane syrup

- Tahini Shake – Dates, tahini paste, cinnamon, chia seeds and shredded coconut, with your choice of milk (soy-almond-coconut)