By Jada F. Smith (@jayduh10)

With additional reporting by Dominek Tubbs (@domnthecity)

In the words of culinary historian Jessica B. Harris, “our history is on the plate.” And as the old folks used to say, she ain’t neva lied.

Dishes like Red Rice and Hoppin’ John descend from the complex agricultural systems that were developed by enslaved Blacks in the American Lowcountry, and were crucial for building U.S. wealth and trade power. The mere existence of a National School Lunch Program speaks to the impact of the Black Panther Party’s revolutionary politics and the broader concept of food security. The fact that fried fish and spaghetti seem to only be popular among Blacks from two places – the Deep South and the Midwest – help tell the story of the Great Migration, one of the largest movements of people in U.S. history.

Curators at The Museum of Food and Drink and The Africa Center in New York are taking that history from plate to palate with the new African/American: Making the Nation’s Table exhibit. Along with an immersive AR (augmented reality) experience in the newly refurbished Ebony Magazine Test Kitchen, the centerpiece of the exhibit is the Legacy Quilt. A towering visual stunner that draws on Black Americans’ use of quilts as both an artistic and archival medium, the Legacy Quilt is a tapestry that shows how Black culinary innovation contributed to American history, politics, economics, nutrition, technology, and more.

Each of the 406 blocks – illustrated by Adrian Franks and stitched by quilters from Harlem Needle Arts with period-appropriate fabrics – tell a story. There is a block for Chef James Hemings (brother of Sally), who introduced French cuisine to American plates. One for Edna Lewis, who pioneered the modern-farm-to-table movement. And another of Frederick McKinley Jones, inventor of a technology that made modern global cold chain transport possible.

There is also a virtual edition of the quilt that creates space for people to submit their own stories of African American culinary heroes, emphasizing the idea that these histories are not finite, and that the work of documenting and celebrating them is ongoing.

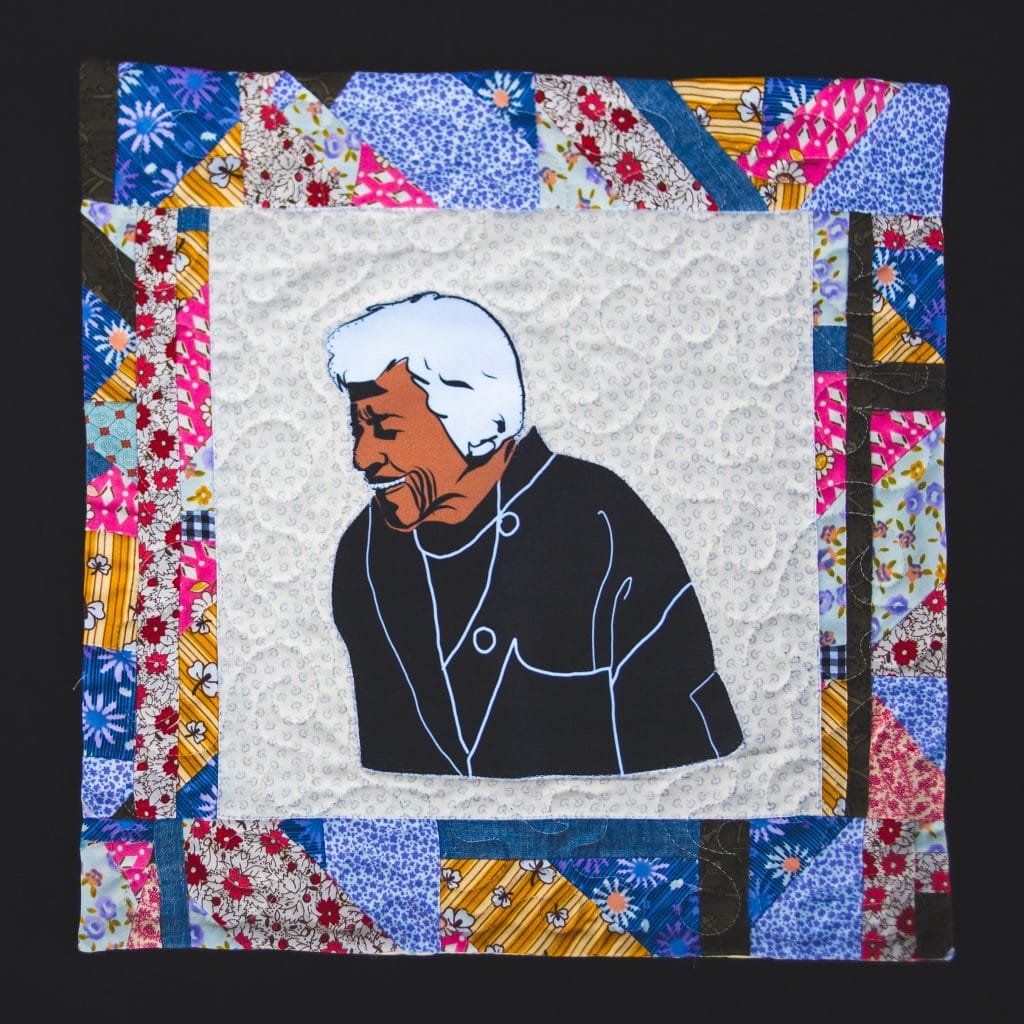

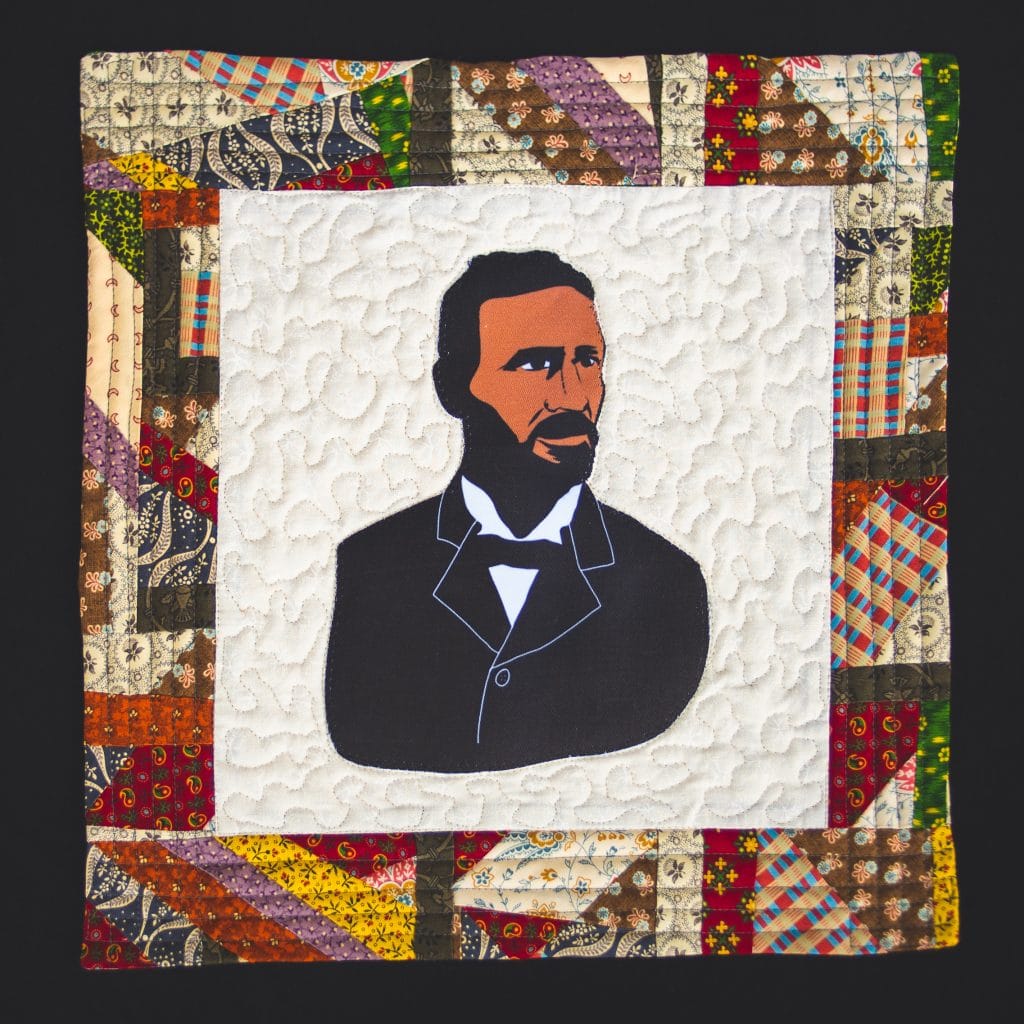

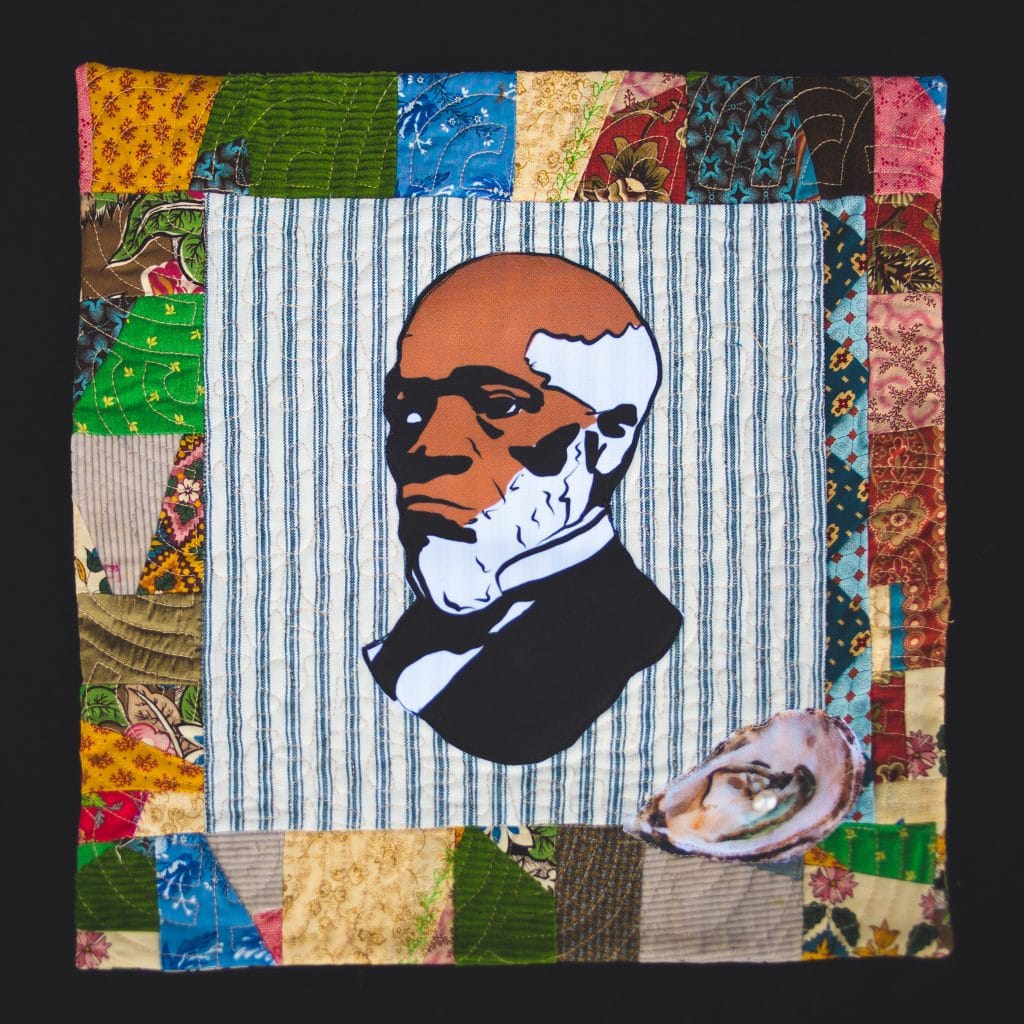

Scroll down to see a few blocks from the quilt, along with accompanying blurbs by writer Osayi Endolyn. Also note that MOFAD is offering a free community membership and access to the exhibition for residents living in the six zip codes surrounding The Africa Center.

Angolan-born Antonio was one of the first Africans to arrive in Jamestown in 1619. He served his indenture for 14 years before changing his name and purchasing his own land. Johnson raised livestock and ultimately grew his estate to 250 acres, a feat for a former servant.

As the chef-owner of Dooky Chase’s in New Orleans, Louisiana, Chase turned a sandwich shop into an upscale restaurant for Creole cuisine, immortalizing dishes like her gumbo z’herbes. Over seven decades, diners included leaders of the Civil Rights Movement, celebrities, and US presidents.

Enslaved Rice Farmers

People from West Africa, where Oryza glaberrima (African red rice) is a native crop, established rice cultivation in the US Lowcountry. These farmers and their descendants created complex agricultural systems including dams and field irrigation.

RELATED: 5 Types of West African Rice

Freda DeKnight

As the first food editor for Ebony magazine, DeKnight presented recipes from across the vast expanse of the African diaspora. Her 1948 cookbook, A Date With A Dish, is considered the first major cookbook written by an African American for an African American audience.

RELATED: How to Caribbean Diaspora Helped Shape Toronto’s Culinary Culture

James Hemings

James Hemings was the first American trained as a French chef. Born enslaved, he spent most of his life cooking for Thomas Jefferson. The Paris-trained chef introduced the US to copper cookware, the stew stove, and dishes such as European-style macaroni and cheese and french fries.

Lillian Harris Dean

After migrating to Harlem, New York City, from the Mississippi Delta in 1901, Dean took money she had made as a cook and launched a food business. Though illiterate, her savvy earned her national praise and the nickname “Pig Foot Mary,” as the pig’s feet and other food she prepared were so popular.

Manna Bernoon

Bernoon opened the first oyster and alehouse in Providence, Rhode Island, as a free black man in 1736, the year of his emancipation. Having opened one of the first restaurants in the US, Bernoon would go on to launch a catering business and tavern.

Nearest Green

The first African American master distiller on record in the US, Green taught Jack Daniel how to make whiskey in Lynchburg, Tennessee. In 1856, as an enslaved man, he refined the Lincoln County process, a charcoal filtration method that makes Tennessee whiskey distinct.

Norbert Rilleaux

Rillieux was educated in France as a free Creole born in Louisiana. He developed a multiple-effect evaporation system that produced higher quality sugar. Planters appreciated the reduced cost, and his invention made sugar cane refinement much safer for enslaved workers.

Thomas Downing

Raised on Virginia’s eastern shore, by free, land-owning parents, Downing was known as the “Black Oyster King of New York.” His popular Broad Street oyster house catered to affluent diners and was world-renowned. The cellars of his restaurant were a stop on the Underground Railroad.

RELATED: 5 of the Best Black-Owned Seafood Restaurants in the U.S.

Warren Luckett

Luckett cofounded Black Restaurant Week in 2016 to support Black-owned businesses in Houston, Texas. In 2019, it expanded to Oakland, Atlanta, Philadelphia, New Orleans, Dallas, and Los Angeles, and proceeds benefited a nonprofit providing legal and technical services to farmers of color.

RELATED: Feed the Soul Foundation Awards $250K to Black-Owned Culinary Businesses

Author: Black Restaurant Week

Content Team